The Rise and Fall of Mount Dagon

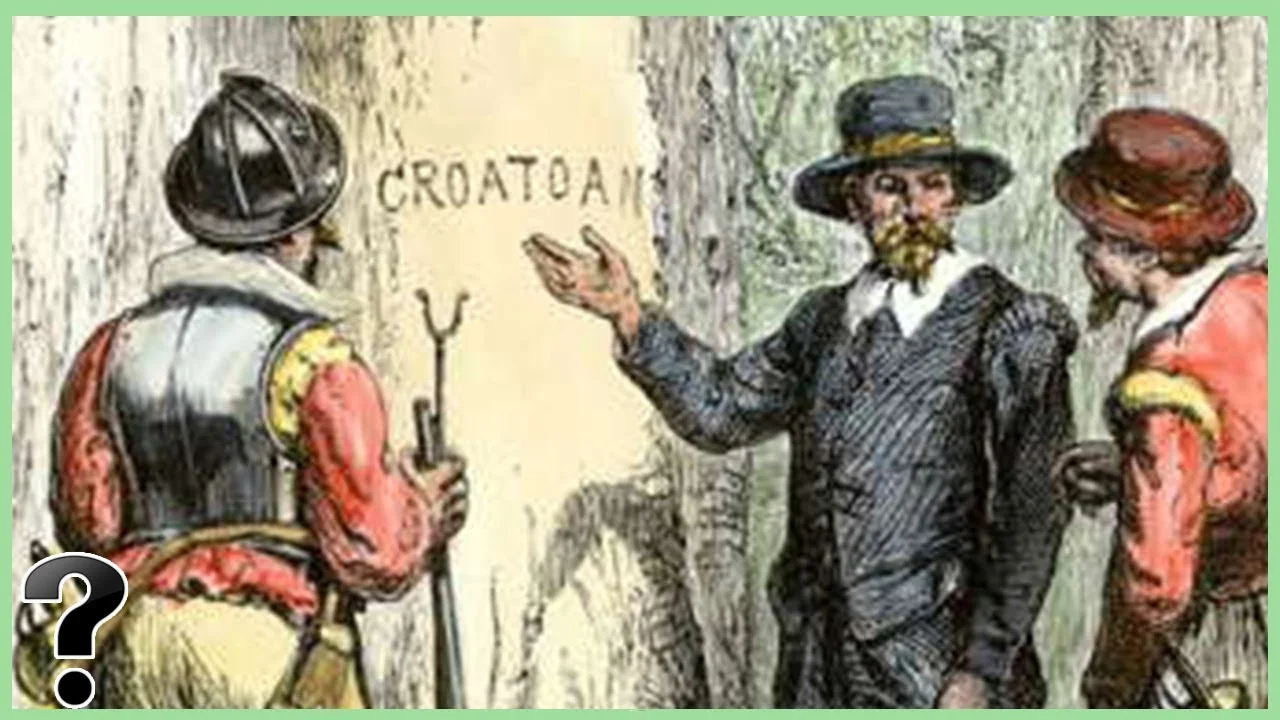

Despite (or because of) the losses the English settlers suffered at Roanoke, European settlement in North America continued in fits and starts, led by entrepreneurs, explorers, and religious refugees. Colonies sprung up at Jamestown, Virginia in 1607, and Plymouth, Salem, and Kingsport Massachusetts, in 1620, 1626, and 1639 respectively. In some cases the colonies overtook lands previously settled by Native tribes and in others they populated previously shunned wilderness. The native tribes of North America had fought their own wars against the ancient and monstrous pre-human sentients who dominated the continent years — and in some cases centuries — before European colonists began to penetrate the coastal frontiers in greater numbers, establishing villages, settlements, and hunting grounds of their own in the few regions not wholly under the domination of these ultraterrestrial beings.

By the 17th century, most Native American tribes had developed a vast corpus of oral history identifying the few lands safe for settlement, passing this knowledge from generation to generation via shamans, elders, and medicine men to ensure that they would continue to maintain their own villages, hunting grounds, and burial places at places far removed from NRE influence. The instinctive need to band together to avoid excessive exposure to the great natural dangers and malevolent alien intelligences that lurked in the shadows of the North American frontier was to be ignored only at great peril, and exposure to the truly profane locales poisoned by their long association with NREs was a greater danger still.

Merrymount

Of course, some of the new colonists came looking for just such haunted hills. The English barrister Thomas Morton built a trading post at one such location in 1625, trading guns and liquor for furs and other supplies from nearby Native tribes from an isolated, hilly peninsula along the Atlantic coast just a few miles from the Puritan colony at Plymouth, roughly at the same location now occupied by Quincy, Massachusetts. Although Morton and his fellow settler’s sale of English weapons to potentially hostile Native tribes from his so-called “Merrymount” colony did little to appease the Plymouth settlers, it was the strange religious rites which Morton and his followers practiced, brought to them by a fur trader known as Richard Billington and the Wampanoag medicine man Misquamicas that finally forced them to act.

By 1626, Merrymount had become infamous as the site of heathen ceremonies and disturbing debaucheries performed by English settlers and Native tribesmen alike in honor of “olde pagan Gods.” According to Plymouth Governor William Bradford’s Of Plymouth Plantation, the residents of Merrymount — English and Native alike — set up rings of stones centered with a May-pole carved with queer images and topped with deer antlers, “dancing about it many days together…as if they had anew revived and celebrated feasts of Gods old when Rome was young, and beastly practices making mad Bacchanalias seem as if child’s play.” Despite a rash of disappearances from Plymouth farms bordering Merrymount territory, the two colonies nevertheless coexisted uneasily for two years, until Morton, probably at Billington’s behest, declared Mayday 1628 the beginning of the “Revels of a New Canaan” and enacted a series of unholy rites and “pagan odes” to the “true Gods of tide and wave.”

Revels of New Canaan

This last blasphemy roused the Puritan colonists to action. The Plymouth Militia under Captain Myles Standish attacked Merrymount that June, taking the town and capturing Morton without a single Puritan casualty, but refused orders to recover certain “ancient scrolls and tomes” Morton and his followers were said to have brought from England. Billington and Misquamicas both disappeared in the raid, and were probably killed in the initial assault. Morton was imprisoned, tried, and then marooned on the deserted Isles of Shoals where his followers continued to secretly supply him with food despite multiple Puritan efforts to ensure that he starved. The sober and fearful Plymouth colonists left the remaining Merrymount settlers to their own devices for nearly a year, evidently hoping that the cult Morton had gathered around himself would disperse if separated from their leader, but did everything they could to isolate and avoid the settlement. It is at this time that Puritan records stop referring to the town as Merrymount; by 1629, Morton’s settlement had instead become widely known as a “place of woe” called Mount Dagon, after the Canaanite sea God its residents were said to have worshipped.

Throughout Morton’s banishment, the Puritan settlements across the Massachusetts Bay Colony were beset with storms and famine, ultimately driving starving settlers from New Salem to raid Mount Dagon once more, destroying the graven May-pole that served as the settler’s “pagan idol” and finding plentiful supplies of corn, wheat, barley, and fish in settlement’s storerooms. Once the supplies were secured, the town was burned to the ground under orders from the Colony Governor, John Endecott, and its remaining denizens forcibly removed from its ruins and resettled elsewhere. This internal migration led several of the surviving families to move North along the coast, with some joining the just-beginning Puritan colony at Salem in 1629, others continuing north to the sheltered harbor that would become Kingsport in 1639, and most of the remainder moving to a fertile coastal plain at the mouth of the Manuxet River, where along with several newly arrived colonists from the southern coast of England they founded Innsmouth in 1643.