The Secret History of the Lost Colony of Roanoke

On 17 August 1585, 107 English colonists set foot for the first time on an island which the local Algonquian speaking tribes called Roanoke, a word they used to refer to the large peculiar and often malformed seashells found on its shores. The colonists immediately built a small fort on the northern tip of the island, claiming it for Queen and Country. It was to be the first step in the creation of a vast British colony in the New World: the birthplace of Virginia, a land so named to honor the expedition’s patron, Elizabeth I. They remained on Roanoke island for less than a year before fleeing to England, complaining of hostile natives, unnatural storms, and “…blasphemous songes on the wind.” It would be nearly two years before another attempt was made to settle the island: those colonists would simply disappear.

The Astronomer

The site of the Roanoke colony had been chosen sight unseen by Thomas Harriot — an Oxford-educated court astronomer, mathematician, linguist, and navigator, and not coincidentally one of the magus John Dee’s proteges — using a series of complex equations that Harriott claimed to have discovered while assisting Dee in his English translation of the Necronomicon in 1581, and confirmed during Harriot’s interviews with two members of a nearby tribe who had been brought back to England by a previous scouting expedition to the outer banks of what is now North Carolina in 1584.

Both the 1584 scouting expedition and the settlement the following year had been sponsored by Sir Walter Raleigh, who held the charter for the Virginia colony from Queen Elizabeth herself. Elizabeth had originally granted the colony’s charter to Raleigh’s half-brother, Sir Humphrey Gilbert. However, in the months and years following Harriot and Dee’s decryption of at least part of Alazrad’s prophecies, Raleigh and the other members of his circle of occultists and scientists, the so-called School of Night — including Harriot, Dee, and the playwright Christopher Marlowe, among others — seem to have set their sights on the colony. According to fragments of a journal attributed to Marlowe now held in the Percy family library at Alnwick Castle, Harriot believed his calculations had pinpointed a land full of green meadows he believed to be a “a reflection of lost Stathilosh,” a location which would “revele mysteries of great importe” to the group; perhaps a reference to the same still lost but apparently ancient city location modern cryptologists have identified as Stethelos in the Greek Pnakotica.

Changing Patrons

With this knowledge in hand, Raleigh persuaded Gilbert to outfit and fund the Virginia expedition. Nevertheless, he was ultimately forced to direct the settlement himself. Gilbert drowned while returning from a successful expedition to Newfoundland in either a strangely fortuitous accident or a well-disguised assassination. Indeed, before his death, Gilbert had also come to believe that the expedition would lead him to discover a secret, mystical knowledge held by the ancients, and was known to have alleged to several contemporaries that he was regularly visited in dreams by the spirits of the prophets Solomon and Job. Although Harriot seems to credit these revelations to a kind of manipulative dream-sending concocted by Raleigh and enacted by Dee, Dee’s own surviving writings make no mention of the visions or of a plot to remove Gilbert, except to note, cryptically, that “that which Henry sees in sleep wears many masks, and none to be trusted.”

Harriot, who did believe Raleigh and Dee had conspired to wrest control of the expedition from Gilbert, does little to explain how, precisely, Raleigh was able to arrange for Gilbert’s death while Raleigh himself was thousands of miles away: Gilbert’s ship sunk with all hands in a sudden storm off the Azores in 1583. Dozens of surviving members of Gilbert’s fleet, upon returning to England, attested that they had seen a massive sea monster with “glaring eyes…sliding upon the water with its whole body” not long before Gilbert and his crew disappeared beneath the waves. Whether Gilbert’s death was accident or murder, Raleigh was left to complete preparations for the Virginia colony.

The New World

Raleigh first organized the 1584 scouting expedition, and upon its success gave command of the 1585 colonial expedition to the experienced mariner Sir Richard Grenville, on the condition that Grenville allow Harriot to accompany the colonists to the New World. It is unclear if Harriot originally intended to remain with the colonists to perform further studies, but after surveying the site and laying out plans for a small fort, Harriot reportedly returned to the fleet and sailed back with them to England, according to one source telling Grenville that he was now “unsure if the colony could fulfill its great purpose.”

Grenville returned to the colony some 10 months later with additional supplies, only to find it abandoned: when fellow English mariner Sir Francis Drake weighed anchor at Roanoke a few months before Grenville’s return, he had offered to take the embattled and weary colonists back to England. To a man, they accepted. The frustrated Grenville, arriving only weeks after the colonists departed, left a small detachment of soldiers on the island to secure the abandoned fort before returning to England once more, planning to return to the island with yet another group of colonists the following year.

This last expedition arrived in June 1587, first stopping on the mainland and then returning to Roanoke island a few weeks later, finding Grenville’s detachment gone, save for a single human skeleton “of seemingly ancient provenance” clad in tattered but recognizable English garb. Despite these ill-tidings,the expedition’s commander, a former Portuguese pirate named Simon Fernandez, ordered 115 new colonists at sword-point to disembark at Roanoke, and then set sail himself shortly thereafter to return to England shortly thereafter. Fernandez’s motives for forcing the colonists to return to Roanoke island are not completely clear, but given the totality of the evidence now available to us, it is more than likely that he was acting under orders from Raleigh, Dee, or Harriot.

Under Threat

Despite the colonists’ attempts to mend relationships with local tribes, deeply hostile after numerous clashes with the previous settlers, the last expedition to Roanoke found itself immediately under threat from unwelcoming neighbors and an almost comically short supply of basic necessities and foodstuffs. Although the prevailing theory has been that the nearby tribes remained hostile to the colonists because of their conflicts with previous expeditions, surviving legend and folklore from the Algonquian-speaking tribes who then lived in the region consistently characterize Roanoke Island — or at least its northern reach, the very site of the twice abandoned Roanoke settlement — as an unholy and dangerous place. Consequently, it may be that the native tribes were trying to warn the colonists of some impending doom, or at least to drive them off so they would not draw the attentions of one or more NREs.

A supposed 1920 U.S. Army Corps of Engineers study of the Roanoke site recently acquired from a private collector broadly suggests that Harriot’s calculations were either mistaken or deliberately incorrect, emphasizing that even a 16th century trained astronomer such as Harriot would have been able to determine that the astronomical alignments over Roanoke in the mid- to late 1580s would have made the site “resonant with Sarnath and Ib” rather than Stethelos. Was Roanoke meant as a sacrifice rather than a legitimate attempt at settlement all along?

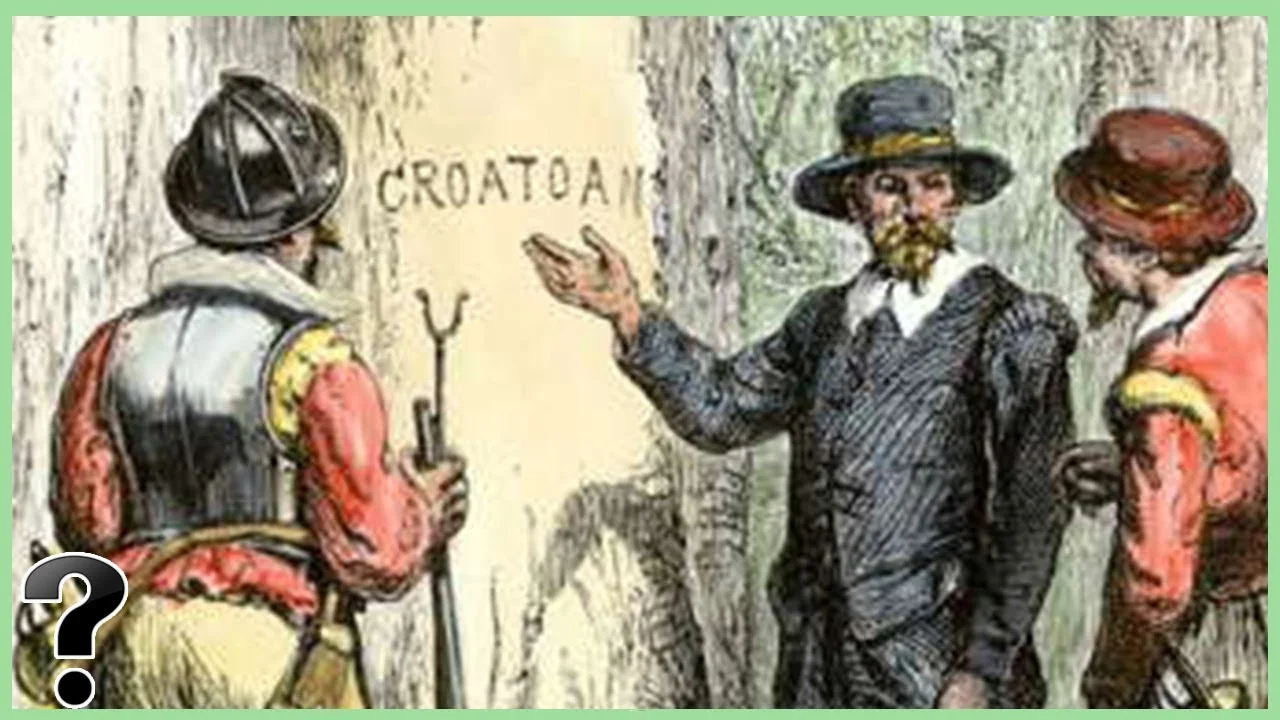

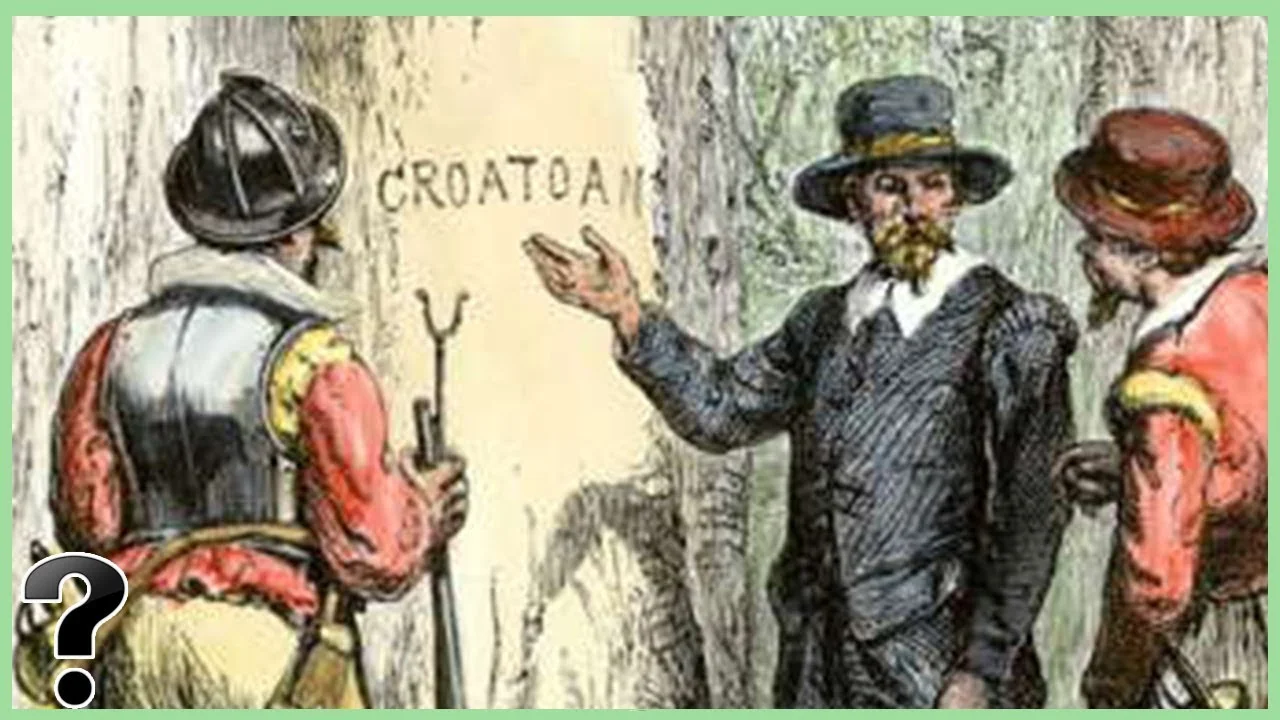

The Doom that Came to Roanoke

Regardless, colony Governor John White took one of the only ships Fernandez had left with the colonists back to England in 1587 to secure additional support for the already precarious settlement effort. White was unable to return until August 1590, and when he finally reached the site of the colony he found it completely dismantled: buildings, tools, and even rudimentary roads gone, as if the entire colony had simply disappeared. A brief investigation revealed no signs of struggle or violence; indeed, the only clue White was able to discover was the word “CROATOAN” — a word from the Sumerian Mnari dialect that roughly translates as DOOM — carved on a tree near the center of the now missing settlement. A sudden storm forced White’s relief fleet away from the island before a more concerted search was undertaken.

The colonists were never found.